Keep Calm and Play On: Video Games That Track Your Heart Rate

Published September 21, 2015 on MIT Technology Review

In a virtual house, you are trapped in an oven, desperately trying to avoid being burned alive. The only way to escape is to take a deep breath, relax, and accept that there are far more disturbing scenarios left to come.

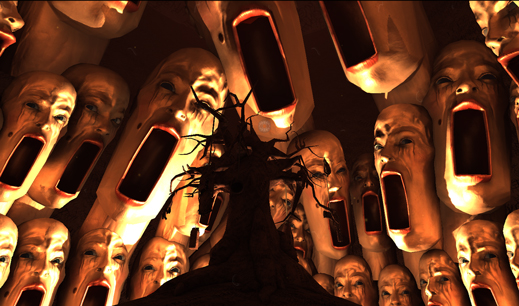

In Nevermind, an indie horror game that will officially be released later this month, players strap on a heart-rate monitor and strive to keep their nerves in check while facing increasingly creepy scenes. Stay calm and cool, and the puzzles progress smoothly. Become even a little jumpy, and the game adds an extra layer of difficulty, such as a vision-obscuring screen of static that only dissipates once the player chills out.

There’s more than just victory at stake here. By triggering unease and then forcing players to calm down in the face of it, Nevermind’s goal is to help players learn how to better manage anxiety and stress, a skill they can use in the real world once gameplay is over.

“As [players] get further in the game, they start to connect: ‘Oh, I notice that when my shoulders are a little bit tense, the game will respond,’” says Erin Reynolds, creative director of Nevermind. “They start to connect what they’re seeing on the screen with those subtle internal reactions that I think so many of us learn to ignore in everyday life.”

Measuring anxiety, and teaching players to conquer it, are two challenges that a new breed of biofeedback game designers are taking on, though there’s no gold standard for how to accomplish either. Nevermind measures heart-rate variability—consistency, or lack thereof, in the intervals between heartbeats—to track when players feel stressed, or “psychologically aroused,” in technical terms. MindLight, a game developed by GainPlay Studio in Utrecht, the Netherlands, uses an EEG reader to figure out when a player is experiencing alpha brain waves, which are dominant during calm and meditative states, or beta waves, which dominate when players feel alert or attentive. Designed for children with anxiety disorders, the game guides players through a spooky mansion, providing them with a magical hat that chases away monsters when players are calm.

Both EEG readers and heart-rate monitors can only detect that there is stress, but not why, making it tough to discern whether players are reacting to fear-inducing content in the game, the difficulty of a level, or some other factor. Reading valence, or the positive or negative emotions associated with that arousal, is a much more technically complex problem, one that Reynolds hopes to solve by building facial recognition capabilities into future versions of Nevermind. MindLight developer Jan Jonk says that valence isn’t a huge issue in his game since it focuses on bringing players down from anxiety and not on triggering it.

Accessibility, however, is a problem. The EEG headset compatible with MindLight costs around $100, while sensors currently compatible with Nevermind cost between $75 for a basic heart-rate monitor that straps to the chest, and about $1,400 for a desktop computer with an Intel RealSense 3-D camera that can detect pulse and control certain features of the game through gesture recognition (see “New Interfaces Inspire Inventive Games”).

One way to increase accessibility is to rely on equipment that users already have. Skip a Beat, a mobile game released last February that teaches players how to keep their heart rate within a specific range, tracks whether a player is excited or calm using the flashlight and camera built into a smartphone or iPod Touch. Light shines through a player’s finger, the camera takes a video, and an algorithm calculates blood flow in the capillaries.

There isn’t much data on whether these games can hone real-world skills that will last, but there may be soon. Reynolds is currently exploring therapeutic uses for Nevermind while Happitech, the makers of Skip a Beat, have partnered with a hospital to investigate whether patients about to go into surgery can lower their heartbeat with the app.

Happitech cofounder Yosef Safi Harb says he expects to see game studios increasingly incorporating biofeedback, though the best ways to do that while preserving player experience aren’t yet clear. “There are really not a lot of examples yet,” he says. “It’s kind of like stabbing in the dark.”