The Psychological Trauma of Defecting from North Korea

Published February 16, 2017 on Nova Next

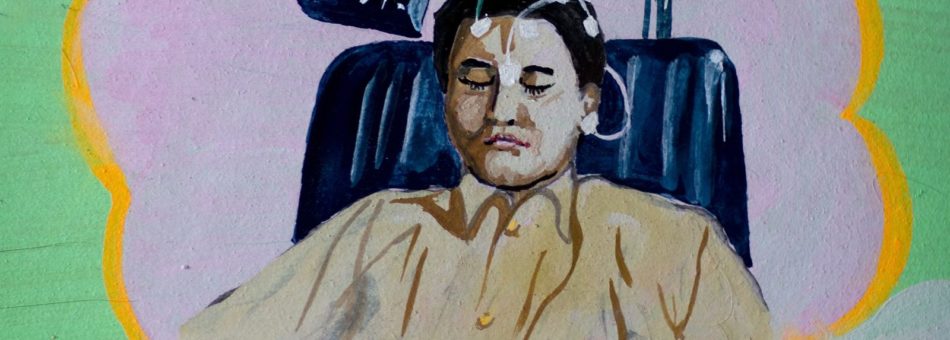

In an apartment in Seoul, South Korea, Lee So-Yeon wakes in the night, thankful that everything she’s just seen is in the distant past.

She dreams of her former life in North Korea, of swimming the icy waters of the Tumen River, of being captured by traffickers in northern China and subjected to a new set of horrors. She dreams of a failed suicide attempt, of being bound and thrown back into the river unconscious, of the North Korean soldiers who dragged her body from the Tumen, keeping her alive but condemning her to 13 days of starvation and physical brutalization in one of the country’s prisons. She dreams of being stripped naked there and forced to lie on a bed with four other women as a guard examined her bodily cavities, keeping the same unsterilized gloves on to search all five women. She dreams of the darkness of her cell, punctuated by smells of her own excrement and compares it to the black of being kicked unconscious by guards.

But she also dreams of release—getting out of prison, swimming the Tumen again, and taking a boat to Seoul, beginning the resettlement process in 2008, two years after her first escape attempt. She dreams of the day when, for the first time, a doctor told her that the nightmares and flashbacks were symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, a condition many defectors face, and the hopelessness and despondency that hung over her waking life were symptoms of depression. Unlike what she was taught growing up, other North Koreans experienced these conditions too, and in Seoul, she could talk about them without fear of being sent to an institution few ever leave.

“They educate people that North Korea is the best, healthiest country in the world. The premise is that there is no one who has any problems mentally,” Lee says through a translator. “There is no concept like depression in North Korea.”

For resettlement and medical professionals working with North Korean migrants like Lee, a major step in providing effective mental health interventions is convincing defectors that the issues they face are diagnosable and treatable. While defectors are generally aware that mental health exists, they know little to nothing about specific conditions, the prevalence of mental health issues, and treatment strategies. Defectors show high rates of psychological trauma. It can be caused by everything ranging from starvation or abuse to fearing capture after resettlement or retribution taken out on loved ones left behind. Despite the suffering, research shows that North Korean migrants are frequently averse to even basic mental health help.

“One of the best ways that North Koreans describe life outside the country to me is that it’s like waking up out of a time capsule,” says Sokeel Park, director of research and strategy for Liberty in North Korea, a non-governmental organization that operates a 3,000-mile underground railroad that picks up defectors in northeastern China and smuggles them to safety. “They go to the bathroom and they don’t know how to use it. They go out into society and people are Korean, and so fundamentally look the same and speak the same language, but it’s like a sci-fi future…It’s a huge culture shock and a lot of things to get used to.”

Developing effective mental health treatment strategies requires understanding attitudes and treatment protocols within the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or DPRK, as North Korea is formally known. Concrete information about the mental health system within North Korea is scarce, but from what is known through defector testimony and limited scientific literature, the DPRK system is modeled after psychiatric practices popularized under Stalin in early 20thcentury, and it’s rooted in suppression and erasure. There, psychiatric conditions are often considered to be the patient’s fault and a source of deep shame for friends and family, says Katharine Moon, a professor of political science at Wellesley College in Massachusetts and a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C. Psychiatric conditions are also inextricably tied to politics and ultimately the country’s caste system, known as “songbun,” Moon adds.

Started in the late 1950s and implemented throughout the ’60s, the songbun system categorized citizens into one of three broad castes: the loyal “core” class, the wavering “basic” class, and the “hostile” class. Castes are designated by two criteria—“ancestral songbun,” which is determined based on the political roles and actions of an individual’s ancestors during the Japanese colonial period and later the Korean War, and “social songbun,” which is determined by the individual’s own loyalty and political orientation. Ancestral songbun is permanent, but social songbun can be modified depending on behavior.

The songbun system is divided into 51 subcategories, according to a 2012 report by the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, and has historically determined a citizen’s access to, and quality of, education, employment, housing, healthcare, and food, among other things. Though the caste system has become more fluid in recent years—primarily due to the rise of black markets which allow some in lower castes to earn money outside of their government-assigned jobs and buy their way into higher society—discrepancies between the castes dictate a significant portion of North Korean life, Moon says. Higher castes enjoy benefits like the ability to permanently live in the capital city of Pyongyang—one of many luxuries that those in lower castes can access with enough money—while lower castes suffer widespread discrimination and are relegated to undesirable jobs. Based on the information that’s available, the songbun system also influences mental health perceptions, Moon says.

“Mental health and politics have become conflated,” she says. “If you come from a questionable line in terms of your political loyalty, then it’s sometimes believed that you’re more prone toward mental health disorders than you are if you come from a revolutionary line.”

Mental Health Inside North Korea

Both the regime and state-run media hide evidence that mental illness exists, says Michael Glendinning, director of the European Alliance for Human Rights in North Korea, a nonprofit defector support organization registered in the United Kingdom. Families have incentive to hide mental illness, too, out of fear that government officials will take steps to remove those considered different from the mainstream.

“There’s not a chance to be open about disabilities,” he says. “There’s not a chance to be open about mental health issues because, if you are, you place yourself and your family members at risk of being pushed out into the northern provinces where things are a lot harder.”

For families, hiding mental illness may also be an act of protection and compassion for the patient. Those with obvious psychiatric conditions run the risk of being sent to state-run facilities called Number 49 hospitals that are often located in remote areas, isolated from the general population, Moon says. Lee So-Yeon confirms that these wards are known throughout the country—when friends are acting strange, North Koreans joke that they’re being “number 49”—but neither citizens nor outsiders know exactly what goes on inside.

Sung Kil Min, a psychopharmacology researcher in Seoul who has interviewed a few medical doctors that have left the DPRK, says that Number 49 hospitals are “very poor” facilities that are “built for keeping ‘mad’ people in custody” and frequently rely on sedatives and antipsychotics to control patients. Lee has not been to a Number 49 ward herself, but says that stories abound in which the seriously sick are tied to their beds and others are forced to do hard labor. Should someone in the labor group deteriorate or get sick due to the strenuous work, they may also be sedated and bound to their bed.

“It’s a vicious circle,” Lee says.

It isn’t clear what exactly North Korean medical schools teach in terms of mental health, but Min says that knowledge of both psychiatry and psychopathology is “very low,” with doctors he’s observed unable to recognize common conditions like depression, anxiety, trauma, and stress. Symptoms of mental health conditions, especially mood and stress-related disorders, are often chalked up to “regulatory dysfunctions of the autonomic nervous system”—which directs unconscious functions such as breathing and heartbeats—and may be treated by internists or neurologists rather than mental health professionals.

“Doctors in North Korea have no access to modern knowledge and training in medical science, no knowledge about new medicines and treatments,” says Joanna Hosaniak, deputy director general of Citizens’ Alliance for North Korean Human Rights. “They don’t have access to internet to teach themselves, so even general medical services are below standards.”

Medical misinformation, shame, and inhumane treatment of those with disabilities have devastating humanitarian consequences, especially in the outer provinces where resources are more limited, Hosaniak says.

“If a child is born with some visible disorder, then usually the doctors inform the parents that this child might be disabled and it’s better to get rid of the child,” she says. “There is infanticide going on. They inform the parents that if you put the child immediately upside down, the child will not be able to breathe after some time and will die.”

These factors, combined with the constant fear and paranoia that comes with living in a surveillance state, all ingrain distrust into the mental fiber of defectors, support organizations report, and serve as sometimes insurmountable obstacles for counselors and healthcare professionals who want to help.

Life on the Other Side

How many people leave North Korea is unknown. China is estimated to hold anywhere from 100,000 to 300,000 defectors while South Korea’s Ministry of Unification calculates their defector population to be over 30,000, with thousands more spread across the globe. Roughly 70% of defectors are female—a factor some link to higher levels of unemployment among North Korean women—and more than half are in their 20s or 30s, in part because people at the peak of their physical fitness are the most prepared to swim rivers and weather the journey.

Resettlement is often the first time that defectors encounter concepts like mental health counseling and treatment, and they process these ideas while learning to exist in a brand new universe. In addition to coping with traumas experienced in North Korea and on the journey out, refugees also contend with learning new languages, laws, technologies, financial systems, and cultural mores, often without being able to contact anyone they know and frequently in countries where they are stigmatized and unwanted. Even in South Korea, where the language is similar to the North Korean dialect, defectors experience significant discrimination. For some, the adjustment is overwhelming and untenable. A few defectors have told the press that they regret their decision, and a very small minority attempt to return to North Korea.

“What you see more is people kind of withdrawing” for a period of time, says Sokeel Park. “It’s kind of like, what do I do now? I’m a fully grown baby in a society. Do I get a job? Do I try and study? Do I try and make friends? It can be an overwhelming paradox of choice… Some North Koreans describe this as all of a sudden having too much freedom.”

To receive resettlement support from the South Korean government, including housing subsidies and help with the citizenship process, defectors must complete a three-month education and assimilation program conducted through the Hanawon resettlement support center. The program includes mental health evaluation and some treatment. After they leave, defectors receive continued support through satellite Hana centers located throughout South Korea.

Even with funded support programs in place, mental health professionals face massive challenges with defectors. A small 2005 study found that nearly one in three defectors in South Korea suffered from PTSD, though some experts believe this figure is low. Depression, anxiety, insomnia, social withdrawal, substance abuse, mood, attention, and stress-related disorders run rampant within North Korean defector communities and are frequently exacerbated by other health problems this population faces. Suicide rates are nearly triple those of South Korean citizens, reports the Ministry of Unification. A separate study found that 70% of defectors did not know the roles of counseling centers or psychological counselors while more than half said the same about psychiatrists.

“When North Koreans arrive here and they are diagnosed that they should continue some sort of therapeutic work with psychotherapy, they usually avoid that,” Joanna Hosaniak says. “They are suspicious. They are afraid of this social stigma. They think that depression, this is something wrong that they have a really serious mental disorder and they are crazy. They don’t trust, very often, these counselors. That is a big problem with the support here.”

Getting through to this population sometimes requires a different approach, Hosaniak adds. Instead of sending refugees directly to a doctor, some organizations train informal coaches to establish a rapport with migrants, build trust, outline basic mental health concepts, and steer migrants towards professionals only after they realize they have a problem and want help.

Effective treatment is also dependent on knowing typical patterns of refugee behavior. Social withdrawal often isn’t immediate. Inability to find work or make friends are warning signs. Wellbeing may slide as refugees become embedded in their new culture, especially in South Korea and other countries where discrimination exists against defectors and mental health treatment in general. The broader scientific literature on the mental health of refugees from other regions of the world shows that home and community-based treatment strategies are generally more effective than office-based counseling. Connecting with others from their home country and continuing culture and traditions from back home can also help refugees gain a sense of belonging.

“They really need someone that they can trust,” Hosaniak says. “The trust is completely broken in North Korea, given the totalitarian regime surveillance and the fear that is everywhere. This is a problem with mental services. You go to a person, a doctor, that doesn’t know you. You don’t trust him, and why would I need to tell my story to that person? What will that person do with that story?”

Eight years after successfully leaving North Korea, Lee So-Yeon is on a mission to spread knowledge about how common trauma and human rights abuses are for defectors. In the process, she hopes to break down the power held by the regime. After completing a decade of military service where she and 30 other women in her unit were raped by a commanding officer, Lee was forced to sell goods on the black market to avoid starvation. While there, she heard an illegal radio broadcast that featured a defector discussing life in South Korea. She began watching foreign television shows and films stored on contraband devices and talking to people who had crossed the border. She began to dream of leaving.

Now, Lee is now a driving force behind the technological infiltration of her former country. The New Korea Women’s Union, a nonprofit organization she co-founded in 2011, records defectors detailing human rights abuses they’ve experienced and discussing life and women’s rights outside of the DPRK. That media is loaded onto USB drives and memory sticks, about 10,000 of which are smuggled into North Korea every year and left in public spaces for anyone to pick up. The New Korea Women’s Union also provides support for those who have already left the DPRK, including job training and psychological counseling. By helping defectors outside of North Korea heal, and increasing education about trauma and the outside world within the DPRK, Lee hopes to steadily chip away at regime’s hold.

“We’re doing the kind of thing the North Korean government hates the most,” she says.